| |

Studies

in Buddhadharma

Emptiness Panacea

to Tsongkhapa the Great

by Wim van den Dungen

Contents

Contents  SiteMap

SiteMap

Table of Contents

|

This book is about emptiness, the core of the Buddhayâna, the ‘vehicle’ of the Buddha. Shûnyatâ is the noun form of the adjective 'shûnya', meaning ‘void, zero, nothing and empty’, from the root 'shi', or ‘hollow’. But emptiness does not mean ‘nothing’, and instead refers to the absence of something, to the fact an object has been negated, is deemed not to be present and nowhere to be found. The zero is not mathematical, as if emptiness would be nothingness, but stands for a second order, pointing to what is not there amongst what is given. What is found wanting ? A certain common way of existence entertained by most of us ... |

|

"Empty should not be asserted.

"Non-empty should not be asserted.

Neither both nor neither should be asserted.

They are only used nominally."

Nâgârjuna : Mûlamadhyamakakârikâ, XXII:11.

"Without contacting the entity that is imputed,

You will not apprehend the absence of that entity."

Śântideva : A Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life, IX.139.

"In order to be sure that a certain person is not present, you must know the absent person. Likewise, in order to be certain of the meaning of 'selflessness', or 'the lack of intrinsic existence', you must carefully identify the self, or intrinsic nature, that does not exist. For, if you do not have a clear concept of the object to be negated, you will also not have accurate knowledge of its negation."

Tsongkhapa : Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path, vol.3, 2.10.

|

Thank You for reading these details of how I have understood emptiness ("śûnyatâ"), the fruit of the religious philosophy of Siddhârtha Gautama, the "prince" of the clan of the Śakya's (ca. 563 - 483 BCE), who, after having completely realized at Bodh Gaya how all phenomena lack inherent existence, entered "nirvâna" and so became known as

Buddha Śâkyamuni, the Awakened One ("bodhi"). Not long after, the extraordinary "dharma" or teaching he proposed touched all walks of Indian life, moving beyond the social system (of casts), appealing to both poor and rich, causing a social revolution. Eventually, it would move outside India and influence countless beings and finally the world at large.

Eliminating the sense of inherent existence or own-form ("svabhâva") is the central cognitive task on the path to awakening, the way to the fruit. Firstly, we need to humble body, speech & mind, allowing the conventional truth about our personal identities to settle in. The self is not a substance, but imputed or designated on the basis of

five impermanent aggregates : sensation (form), feeling, thought, volition & consciousness. The goal is to eliminate the inherent sense of selfhood & personhood (cf. identitylessness of persons). Secondly, one needs to realize the process-like nature of others (cf. identitylessness of phenomena).

A consciousness paying attention to wisdom is a supreme virtuous phenomenon. Once this wisdom-mind realized, there is no longer any need for the path. Buddhahood is irreversible. The universal, ultimate aspect of the view proposed is the realization of what is thoroughly established in the face of other-poweredness, i.e. seeing the permanent emptiness of every functional, conventional, impermanent phenomenon.

The view discussed here is based on the work of Nâgârjuna, Chandrakîrti, Śântideva, Atiśa and Tsongkhapa.

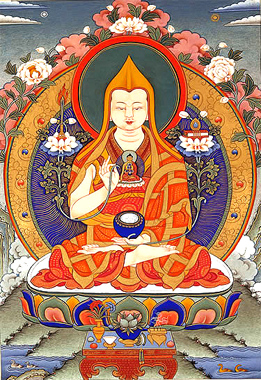

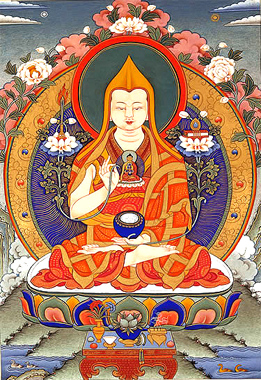

Lama Je Tsongkhapa

"After I pass away,

And my pure doctrine is absent,

You will appear as an ordinary being,

Performing the deeds of a Buddha,

And establishing the Joyful Land, the Great Protector,

In the Land of the Snows."

Śâkyamuni's prediction in the Root Tantra of Mañjuśrî.

Je Tsongkhapa (1357 - 1419) or "Man from the Onion Valley" was a renowned Tibetan Buddhist spiritual reformer, yogi and scholar. Taking layman's vows at the age of three, he was ordained as "Lobsang Drakpa" ("Sumati Kirti" or "Perceptive Mind"), but simply called "Je Rinpoche". He is said to be the reincarnation of Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhâva). Founder of the doctrinal & influential Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, his direct inspiration came from the Kadam school, initiated by Atiśa (985 - 1054) as well as the Sakya school. He also investigated Dzogchen. Based on Tsongkhapa's teachings, the "Yellow Hats" of the Gelug school have two outstanding characteristics :

When he was born in Amdo (northeast Tibet), the grand final compilation of the Canon of Tibetan Buddhism (Kangyur or "Translated Words" &

Tengyur or "Translated Treatises") had just been finished by Bu-ston (1290 - 1364). Tsongkhapa worked through these teachings thoroughly. His work fills eighteen volumes, used as textbooks by succeeding generations. Mastery resulted from (a) the study of the Buddhist teachings, (b) their critical, reflective examination and (c) their realization through meditation.

The major results of this important systematic & complete organization of Buddhadharma (comparable to the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas) were presented in the Lamrim Chenmo (Great Discourse on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment) and the Ngagrim Chenmo (Great Discourse on Secret Mantra). The influence of these works, both available in English, was & is enormous, decisive and lasting. The great monasteries of Tibet, such as Sera, Ganden & Drepung saw the light because of his activities. He also initiated, in 1409, the Great Prayer Festival (Monlam Chemno).

As a Buddhist philosopher, Tsongkhapa attributed the proper logic to the system of the Middle Way founded by Nâgârjuna (ca. 2th/3th century), in particular the Prâsangika-Mâdhyamaka school, and was therefore a skillful teacher of "śûnyatâ", emptiness. His interpretation may be called "Critical Mâdhyamaka", for its central preoccupation is drawing the line between proper and improper objects of negation.

For Tsongkhapa, tradition is not the ultimate authority, but only supportive. The final arbiter is reason, in particular the coherence and elegance within the structure of the itinerary of the spiritual path. Conceptual thought is not rejected but integrated. Not taking in the value of conceptuality is the chief cause of undermining the spiritual path. His conceptual reasonings are based on the rules of classical logic (identity, non-contradiction & excluded third).

It is believed that immediately after his physical death, Lama Tsongkhapa became fully enlightened, i.e. a Buddha. |

The present analysis of emptiness is based on the view on emptiness as expounded in the Middle Way Consequence School, the so-called "Prâsangika-Mâdhyamaka" (or "Rangtong"), in casu :

-

Nâgârjuna (2th CE) in

Mûlamadhyamakakârikâ (A Fundamental Treatise on the Middle Way) &

Shûnyatâsaptatikârikânâma (The Seventy Stanzas on Emptiness) ;

-

Chandrakîrti (ca. 600 – 650) in Mâdhyamakâvatâra (Entering the Middle Way) ;

-

Śântideva (8th CE) in his Bodhicharyâvatâra (A Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life) &

-

Tsongkhapa (1357 - 1419)

in The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment, The Ocean of Reasoning and The Essence of Eloquence.

The view proposed by these authors, in particular Tsongkhapa, forms a coherent whole called "Critical Mâdhyamaka". This tenet, a critical variation on the theme of the Consequence School, will be contrasted with :

(a) the other-emptiness school, the so-called "Shentong" view of the Mountain Doctrine of Dolpopa (1292 - 1391) and the The Essence of Other-Emptiness &

Twenty-one Differences Regarding the Profound Meaning of Târanâtha (1576 - 1634) ;

(b) idealist Mâdhyamaka à la Gorampa, integrating elements from the Mind-Only School (Yogâcâra-Mâdhyamaka) &

(c) Mahâmudrâ & Dzogchen.

The criticism of Tsongkhapa in his Medium-Length Exposition of the Stages of the Path and sections on the object of negation and the Two Truths in his

Illumination of the Thought : Extensive Explanation of "Supplement to Nâgârjuna's 'Treatise on the Middle'" provide the necessary material to show how Critical Mâdhyamaka stands out.

Two crucial differences :

-

realist & idealist views (as in Shentong

other-emptiness & idealist Mâdhyamaka) focus on ultimate truth and downgrade conventional truth ; an ontological rift is posited between the illusionary, contaminated, compounded, conventional realities & our inherent Buddha-nature, primordially pure and luminously aware. These views alienate themselves from conventional truth, deemed illusionary and so invalid, downgrading the necessity of mundane virtue & the cultivation of compassion ;

-

Critical Mâdhyamaka is not ontological, but asks : What mind is wisdom-mind ? Being foremost epistemological, it makes ultimate truth part of the conventional world (pansacralism). Both truths operate the same object but yield different knowledge. Both truths reinforce each other, explaining dependent-arising & compassion. While conventional truth conceals the ultimate truth, appearing otherwise than ultimately, this functional illusion does not invalidate conventional truth insofar as conventional reality goes. Ergo, virtue is guaranteed.

In short, the proposed balancing act implies that :

-

in a logic clearing concepts, both realists & idealists must accept emptiness as absence of inherent existence and so cease to hold the view emptiness can be positively defined by way of an affirming negation (inherent Buddha-qualities, absolute mind, primordial base, clarity, etc.) &

-

in experience, Critical Mâdhyamaka must accept the fruit of Mahâmudrâ, the Great Seal, the direct (yogic) experience of emptiness as the mind of Clear Light. It was Tsongkhapa's intention to move from Sûtra to Tantra. Only the latter offers the definitive experiential content, but this is non-conceptual ! Hence, no definitive statements about it are possible (only mystical poetry remains).

Western Criticism and

epistemology are also taken into account, in casu Kant (1724 - 1804) in the "Transcendental Dialectic" of his Critique of Pure Reason. This will prove to be helpful in order to establish the definition of conventional truth, the cornerstone of Western science. To make Criticism work hand in hand with Tsongkhapa's view on the Two Truths, can only reinforce the logical & critical backbone of the Buddhadharma. To remain open to the experience of the yogis is to allow an ineffable level higher than conceptuality. This nonpartisan approach accepts both philosophical reasoning & yogic (tantric) experience, giving each its proper place (philosophy to clear reification, yoga to direct experience).

To continue to read : Emptiness Panacea (2017)

|

|