Clearings

on critical epistemology

©

Wim van den Dungen

"...

science is apparently increasingly able to construct and reconstruct

itself in response to problem challenges by providing solutions to the

problem ..."

Knorr-Cetina : The Manifacture

of Knowledge, 1981, p.11.

this text forms a triad with :

Behaviours : On Critical Ethics

Sensations : On Critical Esthetics

TABLE OF

CONTENTS

Abstract

Introduction

I : Transcendental Logic :

A. The dyad of formal thought.

B. The fact of reason.

C. The groundless ground of knowledge.

II : Theoretical Epistemology :

01.

The normative solution.

02.

The object of knowledge.

03.

The subject of knowledge.

04.

Categories (mind) & ideas (reason).

05.

Idealistic & realistic transgressions.

06.

Regulations towards unity & expansion.

07.

Correspondence versus consensus.

08.

The coherency-theory of truth.

09.

On methodology.

10.

The fundamental norms of knowledge.

11.

The scientific status of a theory.

12. Metaphysics and science.

13.

Language and the criteria of discourse.

III : Applied Epistemology :

14.

The practice of knowledge.

15. Methodological "as if"-thinking.

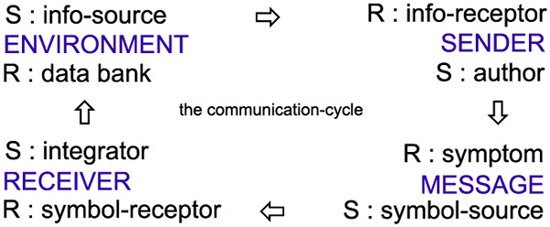

16. Practical communication.

17. Judgments a posteriori.

18. Optimalisations.

19. Producing facts.

20. The opportunistic logic of knowledge-production.

Suggested Reading

Abstract

The various parts of the

equiaeon-system* are assisted by a

critical epistemology. Earlier, its tenets were extensively published in Dutch (Prolegomena,

1994 &

Kennis, 1995), whereas an English

summary was proposed as a set of

Rules of the Game of True Knowing (1999). An application

of these rules in the field of hermeneutics also saw the light (Kennis

en Minne-mystiek, 1994).

In order to develop an ontology, a more rigorous

explicitation of this theory and practice of knowledge is necessary.

This is the aim of the present text, which recapitulates and develops

the epistemological distinctions recently proposed in

Does the Divine exist ? (2005), a

prolegomena to a natural religious philosophy.

The foundational approach of knowledge (stating that "true" knowledge is

rooted in a sufficient ground) is relinquished. True knowledge is

terministic, fallible and probabilistic. No ontology is able to ground

knowledge outside itself. This does not necessarily lead to universal

relativism or skepticism, both avoided.

Indeed, to produce knowledge

which we, for the time being, may consider paradigmatic,

two perspectives are used simultaneously : correspondence with objective reality (experimentation) and

an overall consensus between all sign-interpreters (discourse).

Scientific knowledge is the product of both. They are

the "natural" result of the concordia discors of thought, the

armed truce between subject and object of all possible thought and

the groundless ground of all possible knowledge.

The two possible reductions of this "essential tension" (Kuhn), to wit :

metaphysical

realism & metaphysical idealism, are curtailed.

Metaphysics is deemed a discipline accommodating a total, arguable

picture of the world, assisted by the facts produced by science. Its

nature is not scientific but speculative, its results are not factual

but heuristic, its method is not experimental but argumentative.

These critical ideas, establishing new borders, are "clearings" in the

muddy, confused and dark epistemo-ontological forests of the past and

aim to avoid the recurrent infestation of epistemology by contemporary

materialism and various ideologies (like humanism and spiritualism).

They make the mind aware of its limitations and of its longing after the unconditional and the eternalizing.

For preliminaries read :

Prolegomena (1994),

Kennis (1995),

Rules (1999)

Introduction

§ 1

This introduction serves to highlight a few remarkable historical

landmarks in the field of epistemology, the philosophical study of

knowledge, its possibility and expansion.

Briefly discussing these examples paves the way

for the critical approach (not skeptical, nor dogmatic) fostered in the

main body of this work piece, called in as an epistemological preamble

to a possible ontology.

The choice of what is an outstanding achievement in this domain is

subjective insofar the author was touched by the exemplaric excellence

made present by certain texts. But, these options also cover objective

ground, because at each station, our understanding of knowledge grows.

This

effort is

flanked by

an essay on the existence of the Divine,

concluding in favour of an immanent, conserving cause of the universe

(as in Late Stoic materialist "logos" metaphysics).

On the one hand, strong reliance on a

critical epistemology brings the natural limitations of knowledge to

the fore and so delimits the scope of what there is to be known. The

outcome will be an

immanent stance, one staying within the borders of a possible knowledge. So immanence will be at the core of

this natural

philosophy, however not without reference to the transcendent,

both as a regulative limit-concept (a construct) and an objective

infinity (or absolute absoluteness).

On the other hand, making the

onto-categorial scheme explicit, shows how the proposed naturalism is in

accord with a view on consciousness, information and matter, and this based on

contemporary sciences like physics, biology and psychology. The options

demanded by the scheme give shape to a metaphysical research program at work in the background. By making its tenets clear beforehand, our naturalism

operates without implicit untestable propositions. Being conscious of

them in an explicit way, may avoid their subreptive infiltration in the domain of science

proper (i.e. as part of empirico-formal propositions, which are arguable

and testable).

Both investigations prepare the philosophical

study of nature. Calling this effort "ecstatic" implies (a) the

discovery of traces of the transcendent within the immanent order and

(b) the acknowledgment of the creativity of nature, the urge of all

things to become and develop into greater complexities and this while

introducing novelty. This disclosure will not be prompted by any

metaphysical axiomatics (incorporating such ecstasy a priori, either out of choice or by

adherence to a creed), nor by a theory of

knowledge accommodating ontology (endorsing realism or idealism as the

constitutive ideas of the possibility of knowledge). These unsuccessful

strategies proved to be vain, leading to "perversa ratio", to

quote Kant. Indeed, the critical instrument sought, will be indebted to

nominalism and critical thought. However, although largely

constructivist, it thinks thought as an unfolding process, of which

formal thought is not a priori in conflict with ante-rationality

and meta-rationality, nor does it denies the importance of both in a

multi-dimensional concept of rationality. The latter is in accord with

the author's definition of philosophy.

Philosophy or love of wisdom, is a

multi-dimensional, comprehensive, cognitive answer to this call rooted

in our bio-psychological & spiritual evolution, to knowingly push

limits, transcend limitations, producing more complex, refined & subtle

states of consciousness, information and matter. This answer is

rational, dialogal, open, critical, personal and seeks the

unconditional. Philosophy allows recurrent & multiple transferences

between, on the one hand, reason and intuition or meta-reason, and, on

the other hand, reason and instinct or ante-reason. It is open to the

wonderous, ineffable, luminous, spontaneous & meaningful.

Synopsis

In the course of this intro, salient epistemological perspectives

put forward by the examples, are highlighted in tables.

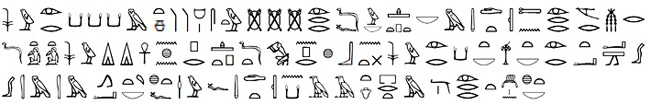

§ 2

Thinking is of all cultures, as are imagination and speculation. But the

solidification of the philosophical approach of thought by thought in

well-formed glyphs or signs (like signals, icons and symbols) is rather

rare. Oral traditions exist, but their historical authenticity cannot be

ascertained, except by testimony. Without signs, imposing a definitive

form upon matter and so leaving a meaningful trace, thought does not in

effect leave the mythical, neither does it initiate history, a traceable

community of sign-interpreters. Even if a scribal tradition is

installed, one needs strong media to ensure historical continuity. If

texts are carved into stone, they are likely to survive better than when

recorded on very perishable materials, like wood or clay. Although the

latter have the advantage of facilitating the speed with which signs can

be

recorded, they nevertheless are less sustainable over long periods of

time. To keep them for posterity, they need to be copied again and again

...

Philosophical cultures become possible when a society has reached the

stage of a leisure-economy, implying that a small elite, close to the

ruling powers, no longer has to work for a living. This upper class is

made free to exclusively perform an intellectual task. Moreover, to

accommodate the formation of schools of thought, an explicit desire to

transmit speculative information must be present in the cultures at

large. This implies a classical language, a scribal tradition, an

educational method, specific buildings, copyists, etc. And these are

costly investments for any society, let be those of Antiquity. In a

historical sense, these philosophical schools become "real" insofar

original texts or reliable testimony are extant.

In Antiquity, speculative thought was never divorced from

religious and ceremonial considerations. In the East, the Vedas

(ca. 1900 BCE)

and their commentaries, the Upanishads (starting ca. 700 BCE), record the musings of the enlightened

seers of India, as well as their Brahmin rituals. But these texts were

recorded on lasting media much later, and their originals are lost.

Were did the first speculative scribal tradition make solid history ?

"Along with the Sumerians, the Egyptians deliver our earliest -though by

no means primitive- evidence of human thought. It is thus appropriate to

characterize Egyptian thought as the beginning of philosophy. As

far back as the third millennium B.C., the Egyptians were concerned with

questions that return in later European philosophy and that remain

unanswered even today - questions about being and nonbeing, about the

meaning of death, about the nature of the cosmos and man, about the

essence of time, about the basis of human society and the legitimation of

power."

Hornung, 1992,

p.13, my italics.

Indeed, in the Middle East, Ancient Egyptian culture, because of its

long and outstanding scribal tradition, brought together a number of remarkable

characteristics. The latter influenced

Western civilization, notably

the pre-Socratic Greeks, a fact our

history books have yet to come to grips with :

-

the words of god and

the love of writing :

it should be emphasized, that

in

Ancient Egypt, both spoken and written

words

were deemed very important : hieroglyphs were "divine words", a

gift of the god Thoth, endowed

with

magical properties, "set apart" and

distinguished from everyday language and writing (namely Hieratic and later

Demotic). They were protected against decay, either by underground tombs,

exceptional climatic conditions or

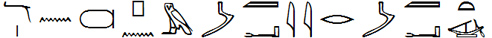

by carving them into hard stone. Pharaoh Unis (ca. 2378 - 2348 BCE), to

assure his ascension and subsequent arrival in heaven, was the first to decorated his tomb with

hieroglyphs, the so-called Pyramid Texts. So even

if the offerings to his double (or "ka") would end, the

hieroglyphs -hidden in

the total obscurity of the tomb- contained enough "inner" power

(or "sekhem") to assure Wenis'

felicity ad perpetuam ...

In its iconicity, Egyptian civilization was quite unique in the

Mediterranean. But, although producing

a vast literary corpus, Egyptian culture never

acquired the

rational mode of cognition. Its attachment to the

contextual and the local (provincial), as well as the special pictorial nature of the

"sacred script", all point to highly iconic, rather "African"

ante-rational mentality ;

-

accomplished discourse :

the fundamental categories of Egyptian

wisdom

were "heart/tongue/heart" insofar as

theo-cosmology,

logoism and

magic were at hand and

"hearing/listening/hearing" in

moral,

anthropological, didactical and

political matters. The first category reflected the excellence

of the active and outer (the father), the second the perfection of the passive

and inner (the son). The active polarity was linked with Pharaoh's "Great

Speech", which was an "authoritative utterance"

("Hu") and a

"creative command" based on "understanding" ("Sia"), which no counter-force could stop ("Heka").

"The

tongue of this Pharaoh is the pilot in charge of the Bark of Righteousness

and Truth !"

Pyramid Texts, utterance

539 (§ 1306).

The passive

polarity was nursed by the intimacy of the teacher/pupil relationship, based

on the subtle and far-reaching encounters of excellent discourse with a

perfected hearing, i.e. true listening.

The "locus" of Egyptian

wisdom was this intimacy. Although Pharaoh was also called "wise", the

sapiental discourses alone name their (possible) author and restrict their

reference to the Divine by using the expression "the god" ("ntr") in the

singular. Wisdom ("saa") was always

linked with a "niche" defined by the vignettes of life the sage

wished to impart as good examples to confer his wisdom to posterity.

"No

one is born wise."

Maxims of Ptahhotep - line 33

The wisdom teachings are

parables helpful to

understand how, in all circumstances, the wise balanced Maat and made the social

order endure by serving "the great house" ("pr aA" or Pharaoh), being at peace with himself

and "the god". This sapiental tradition is not

a fixed canon, and undergoes several transformations ;

-

truth and the plummet of the balance : in Middle Egyptian, the word "maat" ("mAat") is used

for "truth" and "justice" (in Arabic,

"Al-Haq", is both "truth" and "real").

Truth

is an equilibrium (a bringing together hand in hand with a keeping apart), measurable as the state of affairs given by the image,

form or representation of the balance :

|

|

"Pay attention to the decision of

truth

and the plummet of the balance, according to its stance."

Papyrus of Ani

18th Dynasty

Chapter 30B - plate 3 |

This exhortation by Anubis,

the Opener of the Ways, summarizes the Egyptian practice of wisdom and pursuit

of justice & truth. By it, their "practical

method of truth" springs to the fore : serenity, concentration,

observation, quantification (analysis, spatiotemporal flow, measurements)

& recording (fixating), with the sole purpose of rebalancing,

reequilibrating & correcting concrete states of affairs, using the

plumb-line of the various equilibria in which these actual aggregates of

events are dynamically -scale-wise- involved.

This causes (a) Maat to be done for

them and their environments and (b) the proper "Ka", or vital energy, at peace with itself, to flow

between all parts of creation (truth and justice are personified as the

daughter of Re, equivalent with the Greek Themis, daughter of Zeus - cf.

"maati" as the Greek "dike").

The "logic" behind the

operation of the balance involves four rules :

-

inversion

: when a concept is introduced, its opposite is also invoked (the

two scale of the balance) ;

-

asymmetry

: flow is the outcome of inequality (the feather-scale of the

balance is a priori correct) ;

-

reciprocity

: the two sides of everything interact and are interdependent (the

beam of the balance) ;

-

multiplicity-in-oneness

: the possibilities between every pair are measured by one standard

(the plummet).

Although these speculations were embedded in religious thought, an independent

sapiental tradition existed. In the Old

Kingdom (ca. 2670 - 2205 BCE), the scribes were talented individuals

around the divine king and his family. By the Middle Kingdom (ca. 1938 -

1759 BCE), a scribal class emerged. These exceptional thinkers produced

the masterpieces of classical Egyptian

literature. They were attached to a

special building in the temple precinct, the so-called "per ankh" or

"House of Life" (in El Amarna, the "House of Life" abuts upon "the place

of the correspondence of Pharaoh" -

Gardiner, 1938).

§ 3

In the Early New Kingdom (ca. 1539 -

1292 BCE), Late Ramesside

Memphite theology and philosophy (ca.

1188 - 1075 BCE), was

dedicated to Ptah, the god of craftsmen and the patron deity of Memphis.

This theological move balanced the Theban hegemony of the "king of the

gods",

Amun-Re. Memphis was allegedly founded by a

divine king, who, for the first

time around ca. 3000 BCE, if not a little earlier, united the Two Lands,

i.e. Upper (South) and Lower (North) Egypt.

These first kings were the "shemsu Hor", the "followers of Horus"

("Hor" means "he upon high"). Their

names were written within a rectangular frame, at the bottom of which is

a recessed paneling (like on false doors). On top of this "serekh" or

palace facade, was perched the falcon of Horus, hence the appellation

"Horus-name".

The Horus-falcon symbolized the overseeing qualities of the king present in his

palace, representing a transcendent and uniting principle. This bird of

prey glides high up in the sky on the hot air and with a watchful eye

overlooks its large territory, soaring down on its prey at a 100 miles

per hour, combining speed with endurance ...

In the Old Kingdom, Memphis had been the capital of

Egypt and throughout Egypt's long Pharaonic history (ca. 3000 - 30 BCE),

it remained the city where the divine king was crowned. In the Late

Period (664 - 30 BCE), the priests of Memphis were renowned for their

scholarship and wisdom (in his Timaeus, Plato lauds the nearby

priests of Sais, worshipping the goddess Neith). Indeed, Egypt's

sapiental tradition was born in the milieu of scribes and priests.

In Memphis, these thinkers envisioned the process of acquiring knowledge

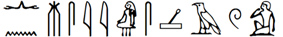

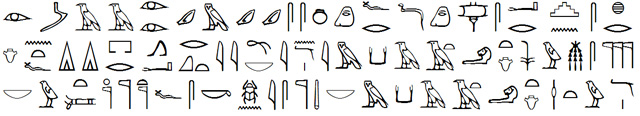

as follows :

"The sight of the eyes, the hearing of the ears, and the breathing of air

through the nose, these transmit to the mind, which brings forth every decision.

Indeed, the tongue thence repeats what is in front of the mind. Thus

was given birth to all the gods. His (Ptah's) Ennead was completed. Lo, every word of the god (Ptah) came into being through the thoughts in the

mind & the command by the tongue."

Memphis Theology,

lines 56-57.

This ante-rational

reflection, by the intellectual elite of Memphis, on the origin of

knowledge, is part of

the

Memphis Theology, a text carved ca. 700

BCE on the

Shabaka Stone exhibited at the British

Museum. It goes back to a lost

original composed between ca. 1291 and 1075 BCE, if not

earlier.

We read how the events recorded by the sense of hearing and

the sense of sight in the living, breathing body are brought up to

the mind (or "heart" =  ). The notion of moving upwards is suggested by the

determinative of the double stairway ( ). The notion of moving upwards is suggested by the

determinative of the double stairway ( / 041), leading to a high place.

This elevated place is nothing less than the realm of the divine mind of

Ptah, to which all possible impressions ascend.

/ 041), leading to a high place.

This elevated place is nothing less than the realm of the divine mind of

Ptah, to which all possible impressions ascend.

The two phases of the empirico-noetic process (registering and

deciding) are put forward. This happens in the context of an affirmation

of the theo-noetic origin of everything. Indeed, the passage is

part of a cosmogony, explaining how every thing came into being by the

divine words uttered by Ptah. Every law of nature (the "netjeru" or

deities) and everything these laws operate, is conceived in the divine

mind and spoken by the divine tongue. Nothing comes into existence

without them.

Although the Aristotelian distinction between the passive and the active

intellect is absent as such (for no formal, abstract concept has yet

been established), it is clear our authors are aware of the

registering faculty of the mind and know that after registering,

the mind produces "every decision", i.e. works to solve problems. These

ideas stand before rationality (ante-rational), because, as is general in

Egyptian thought, they do not fix the

mind in terms of categorial, formal rationality (initiated by the

Greeks). As will be explained later,

ante-rational thought covers the first three stages of human cognition,

namely mythical, pre-rational and proto-rational thought.

The activity of Ptah's divine mind is all-comprehensive. His law

(thought and spoken) is also moral :

"Thus

all the witnessing faculties were made and all qualities determined, they that

make all foods and all provisions, through this word. {Justice} is done

to him who does what is loved, {and punishment} to him who does what is

hated. Thus life is given to the peaceful and death is given to the

criminal. Thus all labor, all crafts, the action of the arms, the motion

of the legs, the movements of all the limbs, according to this command

which is devised by the mind and comes forth by the tongue and creates

the performance of everything."

Memphis Theology,

lines 57-58.

This remarkable theology does not

contemplate a realm of "pure" thought outside of the operations,

contextual limitations, conditionings or determinations of physical reality (a world of ideas, a

Greek

"nous"). Instead of working with a

clear-cut division between object and subject, both are understood as

emerging and co-existing with (not transcending) the context in which

they happen. No formal distinction between facts and so no

decontextualized "theoria" (or contemplation) of events.

The description thus necessarily lacks formal abstraction. So

there is no Greek

Being, Logos, idea of the Good, First

Intellect or Divine mind ("logos"), considered to be radically independent

from and different than the world of the senses and action (in

logic, "formal" means independent of contents). In Egyptian thought, the

"word" only exists when it is spoken ! Like idea and reality, mind and

speech are simultaneous.

|

In Memphite thought, the

impact of mind and speech on both ontology and epistemology is

made clear in ante-rational terms. On the one hand, this is an

idealism avant la lettre, i.e. a proposal in which the

creative and constructivist power of thought and its articulation

are put forward. To conceive something, is to create structures

which determine reality. This ontological idealism is pre-Platonic

and cosmogonic, but exemplifies the importance of (divine)

cogitation, both in terms of understanding (Sia) and authoritative

utterance (Hu). On the other hand, it also underlines, in

realistic fashion, the importance of perception, for the senses

bring their information before the mind and the latter decides. As

usual in Egyptian thought, a multiplicity of approaches is

summoned. Hence, the concordia discors of thought is

already made explicit, albeit in a proto-rational discourse. |

§ 4

The Greek miracle did not fall out of the

sky. By the end of the Dark Age (ca. 1100 - 750 BCE), the Greek cultural

form had already acquired persistent "Aryan", Indo-European

characteristics of its own. Although mythical, they were outstanding

enough to leave their archeological traces.

The Greek mentality had been around before the collapse of the Pax

Minoica (in ca. 1530 BCE, the Thera volcano on Santorini erupted),

and at least emerged at the beginning of the Mycenæan Age (ca. 1600 -

1100 BCE). These Mycenæans were Helladic warlords entertaining an active

commercial economy (based on indirect consumption) and a high level of

mostly imported craftsmanship. They had "tholos" burials, with their

dome shaped burial-chambers. Their palaces followed the architectural

style of Crete, although their structure was more straightforward and

simple.

Their Linear B texts reveal the names of certain gods of the later Greek

pantheon : Hera, Poseidon, Zeus, Ares & perhaps Dionysius. There are no

extant theological treatises, hymns or short texts on ritual objects (as

was the case in Crete). Their impressive tombs indicate their

funerary cult was more developed than the Minoan, and in the course of

their history, outstanding features ensued. Despite the Dorian

devastations and their obliterating and repressing effects, these

persisted :

-

linearization :

"Mycenæan megaron", "geometrical designs",

mathematical form, peripteros ;

-

anthropocentrism : warrior leaders, individual aristocrats, poets, "sophoi" and teachers ;

-

fixed vowels : the

categories of the "real" sound are written down &

transmitted ;

-

dialogal mentality : the

Archaic Greeks enjoyed talking, writing & discussing ;

-

undogmatic

religion : the Archaic Greeks had no sacred books and hence no

dogmatic orthodoxy ;

-

cultural affirmation : the

Archaic Greeks were a "young" people who needed to affirm their

identity ;

-

cultural

approbation & improvement : the

Archaic Greeks accepted to be taught and were eager to learn.

The Egyptian sage never relinquished the religious. The divine was a

given and speculative thought at all times an expression of the deity.

Although deep, remarkable and vitalizing, Egyptian philosophy remained

contextualized and defined by a "milieu" it could not escape.

Exceptional individuals, like

Akhenaten, may have had access to

formal thought. The Ramesside

Hymns to Amun and the

Memphis Theology also testify to this.

Although more than one aspect of Egyptian thought, like the virtual

adverb clause and its

pan-en-theist henotheism, may assists

speculative naturalism, no systematic approach of wisdom ever gained

ground.

The Indo-European mentality of the Archaic Greeks differed from the

African tradition (of which Egyptian thought was the best example).

Between ca. 750 and 600 BCE, we find the crystallization of their

city-states and the rise in power of the non-aristocrats, allying

themselves with frustrated noble families and putting the hereditary

principle under pressure. The two main leitmotivs of this age are

discovery (literal and figural) and the process of settlement &

codification. In some towns, a leisure-economy ensued, and with it, the

free time to speculate.

The influence of Egyptian thought on Thales of Milete (ca. 652 - 545

BCE) and Pythagoras of Samos (ca. 580 BCE - 500) has been studied

elsewhere.

Despite these and many other influences, the Greeks developed their own

systematic, linearizing approach. They focused on :

-

Milesian

"arche", "phusis" & "apeiron" : the elemental laws of

the cosmos are rooted in substance, which is all ;

-

Pythagorean

"tetraktys" : the elemental cosmos is rooted in numbers

forming man, gods & demons ;

-

Heraclitean

"psyche" & "logos" : becoming and a

quasi-reflective self-consciousness, symbolical & psychological,

prevail ;

-

Parmenidian

"aletheia" : the moment of truth is a decision away from

opinion ("doxa") entering "being" ;

-

Protagorian

"anthropos" : man is the measure of all things and the

relative reigns.

From the start, ontological questions dominated Greek thought. What is the

"physis" or fundamental stuff of nature (Ionic branch) ? How to know the

truth as "being" (Eleatic branch) ? Can indeed anything truly be known

(Sophists) ? Why is there something rather than nothing (Plato,

Aristotle) ?

§ 5

Parmenides of Elea (ca. 515 - 440 BCE), inspired by

Pythagoras and pupil of Xenophanes (ca. 580/577 - 485/480 BCE), was the

first Greek to develop, in poetical form, his philosophical insights about truth

("aletheia"). Thanks to the neo-Platonist Simplicius

(490 - 560), 111 lines about the Way of Truth are extant. In it, the

conviction dominates that human beings can attain knowledge of reality

or understanding ("noos"). But to know the truth, only two ways are open :

the Way of Truth and the Way of Opinion. These are defined in terms of

the expressions "is" and "is not".

The first is the authentic way, leading to the unity and uniqueness of

"being". When using the copula "is", Parmenides points to the perfect

identity of substantial "being", ascribed in a single sense. Hence, what

is other than "being" itself has no being at all ... This is the second

way, that of mere opinion ("doxa").

To develop his argument, Parmenides uses a three-tiered disjunction. To

answer the question : "Is a thing or is it not ?", three answers are

possible : (a) it is or (b) it is not or (c) it is and it is not.

By using the necessities of logic, the formal conditions of knowledge

become apparent. Two ways of inquiry are alone conceivable. The first,

the journey of persuasion, attends on reality, on the fact a thing is,

while the second, is without report and deals with that a thing is not

and must not be. As one can neither know what is not (deemed

impossible), nor tell of it, the second way is pointless. Only one story

of the way is left : "being" is ungenerated, imperishable, entire,

unique, unmoved and perfect. It never was nor will be, since it is now

all together, one, indivisible. It has no parentage.

Let us consider the three answers. If a thing is and is not, then this

either means that there is a difference due to circumstance or that

"being" and "nonbeing" are different and identical at the same time.

This answer is relative (circumstantial) or contradictory. If a thing is

not, then it cannot be an object of a proposition. If not, not-being

exists ! This answer is pointless. As the last two answers are clearly

false, and only three answers are possible, so the first answer must, by

this reductio ad absurdum, be

true, namely : the object of thought "is" and equal to itself from every

point of view.

With Parmenides, pre-Socratic thought reached the formal stage of

cognition. Before the Eleatics, the difference between object and

subject of thought was not clearly established (cf. the object as

psychomorph). The formal laws of logic were not yet brought forward and

used as tools to back an argument. The strong necessity implied by the

laws of thought had not yet become clear. Ontologically, the

proto-rational concept of change of Heraclitus (540 – 475 BCE) is

indeed opposed to the static, single being of Parmenides, but

epistemologically, the latter was the first to underline the importance

of the formal characteristics a priori of all thought. The

mediating role of the metaphor is replaced by an emphasis on the

distinction between the thinking subject (and its thoughts) and the

reality of what is known.

"... remaining the same and in the same state, it

lies by itself and remains thus where it is perpetually, for strong

necessity holds it in the bondage of a limit, which keeps it apart,

because it is not lawful that Being should be incomplete, for it is not

defective, whereas Not-being would lack everything. The same thing is

for conceiving as is cause of the thought conceived ; for not without

Being, when one thing has been said of another, will You find

conceiving. And time is not nor will be another thing alongside Being,

since this was bound fast by fate to be entire and changeless."

Parmenides, fragment 8, 29-35.

§ 6

Ironically (or by force of apory ?), the idealism of

Parmenides, thinking the necessity of the object of thought, confuses

between a substantialist and a predicative use of the verb "to be" or

the copula "is". That something "is" (or "Dasein") is not identical with

what something "is" (or "Sosein"). Properties (accidents) do exist apart

from the "being" of the substances they describe.

From the substantialist point of view, not-being is pointless. Only an

all-comprehensive "Being" can be posited. We know Parmenides

asserted further predicates of the verb "to be", namely by introducing

the noun-expression "Being". The latter is ungenerated, imperishable,

complete, unique, unvarying and non-physical ...

He did not conceive the absence of certain properties as not-being, nor

could he attribute different forms of "being" to objects. What

Parmenides calls "Being", is an all-comprehensive being-there standing

as being-qua-being, as "Dasein" in all the entities of the natural world

(and their "Sosein"). In that sense, namely in his mysticism, he is

closer to Heraclitus as one would suspect.

If Parmenides core interest was formal, then he mainly wanted to show

what sense attaches to the verb "to be" in asserting and thinking. But

modern exegesis attributes to his thought an existential understanding

of the verb, or worse, an archaic failure to distinguish between both

uses.

The difference between object and subject of thought, at the core of

formal rationality, allows for two radical reductions : an object

without a subject and a subject without an object.

Without object, thought cannot say anything about the world and its

propositions are all tautologies and analytical. None of the accidents

refer to anything outside thought, to an entity, so must we think, which

is kickable and which kicks back. In an all-comprehensive subjectivism,

the sole laws are the formal rules themselves, pointing to a set of

ideas. Lack of object is an outstanding characteristic of idealism.

Without subject, observation is impossible. For there can be no

observation without an observer and no two observers occupy the same

space-time. Moreover, there is no observation without interpretation. The

thinking subject is an integral part of the act of observation.

Theoretical connotations co-determine what is observed (even in the

brain, various levels of sensoric interpretation are at work). In an

all-comprehensive objectivism, sense-data are the sole bedrock, pointing

to a real world out there. Inability to regard the constructed nature of

reality is the outstanding feature of realism.

As soon as formal rationality envisaged the crucial difference between

object and subject of

thought, the apory resulting from radical reductions became possible. As

a result of the continuous complexification of thought, these extreme

positions were and are still advocated. Grosso modo, realism in

materialism and the natural sciences, idealism in humanism and the

sciences of man. It is one of the tasks of epistemology to elucidate

this concordia discors and make it operational in terms of the

growth of knowledge.

§ 7

"All thinkers then agree in

making the contraries principles, both those who describe the All as one

and unmoved (for even Parmenides treats hot and cold as principles under

the names of Fire and Earth) and those too who use the rare and the

dense. The same is true of Democritus also, with his plenum and

void, both of which exist, he says, the one as being, the other as

not-being. Again he speaks of differences in position, shape, and order,

and these are genera of which the species are contraries,

namely, of position, above and below, before and behind ; of shape,

angular and angleless, straight and round."

Aristotle : Physics, book 1, part

5.

Democritus of Abdera (ca. 460 - 380/370 BCE),

geometer and known for his atomic theory, developed the first

mechanistic model. His system represents, in a way more fitting than the

difficult aphorisms of Heraclitus, a current radically opposing Eleatic

thought.

The evidence of perception cannot be denied. The Eleatics are obviously

wrong. Instead of relying on the formal conditions of thought only, the

origin of knowledge is given with the undeniable evidence put forward by

the senses. Becoming, movement and change are fundamental. Hence,

not-being exists. It is empty space, a void. If so, then being is

occupied space, a plenum. The latter is not a closed unity or

continuum, a Being, but an infinite variety of indivisible particles

called "atoms".

The atoms are all composed of the same kind of matter and only differ

from each other in terms of their quantitative properties, like

extension, weight, form and order. They never change and cannot be

divided. For all of eternity, they cross empty space in straight lines.

Because these atoms collided by deviating ("clinamen") from their paths,

the world of objects came into existence (why they moved away from their

linear trajectories remains unexplained). Hence, the universe is

composed of a multiplicity of atoms moving and colliding in empty space

... Each time this occurs, they form a vortex separated from the rest of

the universe, thus forming a world on its own. Hence, an infinite number

of simultaneous and successive worlds are in existence.

Objects emerge by the random aggregation of atoms. Things do not have an

"inner" coherence or "substance" (essence). Everything

is impermanent

and will eventually fall apart under the pressure of new collisions. Atoms are characterized by quantitative features only. Thus, all

spiritual, psychological and mental processes can be reduced to

conglomerates of atoms moving without inner principle of unity.

Thoughts, feelings, volitions and the like, are nothing more than

mechanical activities between atoms. Qualities are subjective

interpretations of quantities. Hence, the universe is material,

quantitative, deterministic and without finality.

Regarding knowledge, Democritus conjectures the senses are all

derived from the sense of touch. The atoms bombard the senses and give a

picture of the object emitting them. As a function of their speed, form

etc. we can speak of sweet, blue etc. These names are only conventional

and do not convey any real characteristic of the object in question.

But, we are able to discover the true, real features of a thing behind

the dark veil of the senses. This is intellectual knowledge. Indeed,

without the latter, it would not be possible to develop the mechanistic

model !

The logical difficulty facing this model is clear : if all things are

atoms, then how can rational knowledge be more reliable than perception ?

Moreover, how can atomism describe atoms without in some way

transcending them ? In epistemological terms : how can the subject of

knowledge be eclipsed hand in hand with a description of this "fact" ?

There is a contradictio in actu exercito : although refusing the

subject of knowledge any independence from the object of knowledge, the

former is implied in the refusal.

The problems facing Democritus are those of realism (materialism) in

general. They mirror those of Eleatic idealism (spiritualism). In

pre-Socratic philosophy, both represent the two poles of the essential

tension characterizing thought.

|

The pendulum-swing between

realism and idealism, or, in other words, the exorcism of

respectively either subject or object of knowledge, can be

identified in pre-Socratic thought as the apory between Parmenides

& Democritus. Both exemplify a movement of thought allowing it to

exceed and thus reduce (repress) its natural anti-pode. Idealism

rejects the object of perception, realism the constructive activity

of the subject of thought. Instead of harmonizing both, by

introducing a principle of complementarity, thought is crippled by

a contradiction. In each case, the necessities lay bare by this

forced monism (either of mind or of matter), bring the structure

of both poles to the fore : Parmenides thinks the logical

conditions a priori, leading to oneness, universality and

qualitative uniqueness, Democritus observes the empirical

conditions a posteriori, bringing in an infinite series of

singular atoms and quantitative multiplicity. |

§ 8

The Eleatic effort to posit the necessity of logic &

unity was turned into rhetoric by the wandering Sophists. By so introducing the relativity of thought (skepticism

and humanism), they prompted a new quest for a comprehensive system. In it, the various facets developed

since Thales would have to be brought together in such a way that

true knowledge would remain certain and eternal (and not

circumstantial and probable).

"Nothing exists. If anything existed, it could not

be known. If anything did exit, and could be known, it could not be

communicated."

Gorgias of Leontini : On What is Not,

or On Nature, 66 - 86.

Greek concept-realism, in tune with the

tendency of thought to

fossilize and substantialize, developed two radical

answers and

two major epistemologies. These were foremost intended to serve

ontology, the study of "real" beings and being, as does the logic

that underpins them. Indeed, neither Plato or Aristotle developed the

quantitative view of the world as proposed by Democritus. Their systems

are devoid of mathematical physics.

In concept-realism, concepts must refer to something "real".

Our thoughts are always about some thing. The "real" is a sufficient ground guaranteeing the identity of

every thing. For the Greeks, the "real" had to be universal ("ta

katholou", or applicable everywhere and all the time). Either these

universals exist by themselves outside the sensoric world (the real is

ideal) or they only exist as the form of things in each individual thing

(the ideal is real). In the former, a cleavage occurs and dualism

emerges (between being and becoming), in the latter, a monism ensues.

Again two reductions of the ongoing, crucial tension of thought, i.e.

the continuous, shocking confrontations between object and subject of knowledge

: the concordia discors.

For Plato (428 - 347 BCE), strongly influenced by Pythagoras and the

Eleatics, there is a real, Divine world of ideas "out there" or,

as in neo-Platonism,

"in here", a transcendent realm of Being, in which the things of this

fluctuating world participate. Ideas are those aspects of a thing which

do not change.

Obviously then, truth is the remembrance (anamnesis) of (or return to) this eternally good

state of affairs, conceived as the limit of limits of Being or even

beyond that. These Platonic ideas, like particularia of a higher

order, are no longer the truth of this world

of becoming but of another, better world of Being, leaving us

with the cleaving impasse of idealism : Where is the

object ?

The Platonic ideas exist objectively in a reality outside the

thinker. Hence, the empirical has a derivative status. The world of forms is

outside the permanent flux characteristic of the former, and also

external to the thinking mind and its passing whims. A

trans-empirical, Platonic idea is a paradigm for

the singular things which participate in it ("methexis"). Becoming

participates in Being, and only Being, as Parmenides taught, has reality.

The physical world is not substantial (without sufficient ground) and

posited as a mere reflection. If so, it has no true existence of

its own (for its essence is trans-empirical). Plato projects the world of

ideas outside the

human mind. He therefore represents the transcendent pole of Greek

concept-realism, for the "real" moves beyond our senses as

well as our minds. To eternalize truth, nothing less will do.

Aristotle (384 - 322 BCE) rejects the separate, Platonic world of real proto-types, but not

the "ta katholou", the generalities ("les généralités", "die

Allgemeinen"), conceived, as concept-realism demands, in terms

of the "real", essential and sufficient ground

of knowledge, the foundation of thought. So general, universal ideas

do exist, but they are always immanent in the singular things of this world.

There is no world of ideas "out there". There is no cleavage

in what "is" and there is only one world, namely the actual world

present here and now. The indwelling formal and final

causes of things are known

by abstracting what is gathered by the passive intellect, fed by

the senses, witnessing material and efficient causes. The actual process of abstraction is performed by the

intellectus agens, a kind of Peripatetic "Deus ex

machina", reflective of the impasse of realism : Where is the

subject ?

"The faculty

of thinking then thinks the forms in the images, and as what is to be

pursued or avoided is already marked out for it in these forms, the

faculty can, by being engaged upon the images, be moved, and this also

in a way independent from perception."

Aristotle : De Anima, III.7.

How is this first intellect able to derive by abstraction the universal

on the basis of the particular ? How does it recognize the forms in the

images without (Platonic) proto-types ? Even a very large number of particulars

does not logically justify a universal proposition, as Aristotle knew. Induction has no

final clause, for all past causes can never be known. How does this

active intellect then recognize the similarities between properties offered

by the passive intellect, if not by virtue of a measure which is

independent from perception

(and so again introducing a world of ideas) ?

Aristotle posits the objective forms in the actual world. In the latter,

both being and becoming operate. This was a major step forward, for

ontological dualism is explicitly avoided, although implicitly

reintroduced within psychology. The forms are realized in singulars, but known by

accident of a universal intellect he does not study. For him, the "real"

is known through the senses and the curious abstracting abilities of the

mind. The workings of the intellectus agens remain dark. This

concept-realism is immanent.

All things are explained in terms of four causes : causa

materialis, causa efficiens, causa formalis and causa finalis.

Experience of the first two causes, triggers the process of cognition

and knowledge of material bodies. Abstracting the last two causes,

allows one to understand the "form" or essence of things.

In Platonic concept-realism, one cannot avoid asking the question :

How can another world be the truth of this world ? The ontological

cleavage is unacceptable. Peripatetic thought

summons a psychological critique, for how can the human soul possibly

know anything if not by virtue of this remarkable active intellect ? Both

reductions are problematic. Because they try to escape, in vain, the

Factum Rationis, and so represent the two extreme poles of the

concordia discors of thought, they form an apory. Plato, being an idealist,

lost grip on reality. Aristotle, the realist, did not fully probe

his own mind. Composite forms of both systems do not avoid the conflict,

although they may conceal it better. The crucial tension of thought was

not solved by Greek concept-realism. How to evolve formal rationality

?

|

The two major

philosophical systems of Greek philosophy are examples of

foundational thinking. Truth is eternalized and static.

Concept-realism will always ground our concepts in a reality outside

knowledge. Plato cuts reality in two qualitatively different

worlds. True knowledge is remembering the world of ideas.

Aristotle divides the mind in two functionally different

intellects. To draw out and abstract the common element, an

intellectus agens is needed. But, both positions reveal new

insights : knowledge is impossible without innate forms (Plato)

versus knowledge starts with perception (Aristotle). Greek thought

is unable to reconcile the extremes and so no armed truce ensued.

One tried to avoid the concordia discors by eliminating the

other side of the equation. These tensions, like open wires,

short-circuited Medieval logic, preparing thought for its

emancipation from fideism and fundamental theology. |

§ 9

In Late Hellenism, and particularly in Stoicism, language became an

independent area of study. Logic was not longer embedded in metaphysics,

but part of the new science of language (linguistics). The technical

apparatus

developed by the Platonic and Peripatetic schools, as well as the

mechanics of logic had been fully mastered. An overview of knowledge was

sought, and concept-realism still prevailed. Concepts were either rooted in

universal ideas or in immanent forms. Both ideas and forms were "real",

i.e. agents working "outside" the mind and delivering the

foundation of thought and true knowledge. Throughout the Mediterranean,

the Egyptian school of Alexandria was renowned. In 529, under the

Christian emperor Justinianus, who commissioned the Hagia Sophia, the

Platonic Academy at Athens was closed.

Physics studies things

("pragmata" or "res"'), whereas dialectica and

grammatica study words ("phonai" or "voces"). This is the

approach of the first scholastic and the last Roman, Boethius (480

- 524 or 525).

He created the term "universalia" (the Latin of

"ta katholou") to denote the logical concepts genus and

species. The apory between Plato's world of ideas and

Aristotle's immanent forms, is no longer part of the Stoic context. A

simplification took place which brought logic and linguistics to the fore.

In his Isagoge, a work translated by Boethius, Porphyry (232/3 -

ca. 305)

had written :

"I

shall not say anything about whether genera and species

exist as substances, or are confined to mere conceptions ; and if they

are substances, whether they are material or immaterial ; and whether

they exist separately from sensible objects, or in them immanently."

Porphyry : Isagoge, 1,

introduction.

For Boethius, considering these matters to be "very deep", the answer is Aristotelian : the universals have an

objective existence in particular physical things, but the mind is able

to conceive genera and species independent of these

bodies.

For Isidore of Sevilla, who died in 636, etymology was the crucial science,

for to know the name ("nomen") of an object gave insight into its

essential nature. Hence, there exists an implicate adualism between the name

(or word) and its reality or "res". This symbolic adualism does

not differentiate between an "inner" subjective state of

consciousness and an "outer"

objective reality, which is a typical characteristic of ante-rationality

(cf. psychomorphism). This view was a return to Plato and the Eleatic

cleavage between "is" and "is not". And indeed, this Platonism

accommodated the Augustinian interpretation of Christianity. Here,

symbolical adualism walks hand in hand with ontological dualism : the

true name of a thing reveals its unchanging, transcendent essence

intuitively, precisely because there is a radical division between the

perfect, true world of Being and the incomplete, false world of

becoming.

Thanks to the Carolingian Renaissance, and the organization of the

Palatine School, a remote ancestor of the Renaissance "university"

("turned towards unity") was created. Europe, under the political will

of Charlemagne, was awakened to its "rational" inheritance and embraced

the importance of education and learning (for the upper classes).

Although short-lived, its influence would not completely vanish.

Clearly the problem of universals touched the foundation of fideist thought, which tried to identify general names (like "God")

in the mind with universal objects in reality. On the one hand, there

was

the ultra-realistic position, or "exaggerated realism", found in the

De Divisione Naturae of John Scotus Eriugena (ca. 810 - 877) and the

work of

Remigius of Auxerre (ca. 841 - 908), who taught that the species is a

"partitio substantialis" of the genus. The species

is also the substantial unity of many individuals. Thus, individuals

only differ accidentally from one another. All beings are thus

modifications of one Being. A new child is not a new substance, but a

new property of the already existing substance called "humanity"

(a kind of monopsychism avant la lettre may be noted).

On the other hand, very soon heretics in dialectic rose. For Eric

(Heiricus) of Auxerre (841 - 876), general names had no universal

objects corresponding to them. Universals concepts arise because the

mind gathers together ("coarctatio") the multitude of individuals

and forms the idea of species. This variety is again gathered

together to form the genus. Only individuals exist. By the process

of "coarctatio", many genera form the extensive concept of

"ousia" ("substantia"). In the same line, Roscelin (ca. 1050 -

1120) held that a universal is only a word ("flatus vocis") and

so "nihil esse praeter individua" ...

§ 10

In the Middle Ages, this apory between exaggerated realists ("reales") and

nominalists ("nominales"), itself a logico-linguistic

transposition of the ontological apory between Plato and Aristotle, is best illustrated by the confrontation

between William of Champeaux (1070 - 1120), and Abelard (1079 - 1142).

The latter was

a rigorist dialectic arguing against the "antiqua doctrina", and,

according to the famous Bernard of Clairvaux (1090 - 1153), an agent of

Satan !

Abelard argued, that according to William of Champeaux, only ten

different substances or "essences" exist (namely the 10 categories of

Aristotle). Hence, all living beings, subsumed under "substance", are

substantially identical, and so Socrates and the donkey Brunellus are

the same.

In his early days, William of Champeaux taught, against his teacher Roscelin, that

the individual members of a species only differ accidentally from

one another. But this identity-theory came under severe attack and so he

changed it. Some say as a subterfuge, William later replied to Abelard with his

indifference thesis, according to which two members of the same

species are the same thing, not "essentialiter" but "indifferenter".

Peter and Paul are "indifferently" men (they thus possess humanity "secundum

indifferentiam"), because as Peter is rational, so is Paul, whereas

their humanity is not the same, i.e. their nature is not numerically the

same, but like ("similis"). In fact, he is saying the

universal substances of both are alike, applying indifferently to both

or any other man. This position was also part of Abelard's polemical

interpretations.

Abelard's "nominalism" is a denial of ultra-realism in epistemology,

i.e. against the adualism between "vox" and "res". He does not refute Platonic

"ideae" preexisting in the mind of God, but understands these as

the metaphysical foundation of the real similarities in status between

objects of the same species, and not of the objects (as Platonism

insists). So the ideas explain how two things may be alike, but objects

do not participate in ideas, nor are these ideas the "ousia" or

"substantia" of objects.

Abelard's analysis states the distinction between the logical and the real

orders, but without the denial of the objective foundation of the

universals. This early nominalism is a moderate realism. He demonstrated

how one could deny exaggerated realism without being obliged to reject

the objectivity of genera and species.

For Abelard,

universals were by nature inclined to be ascribed to several objects.

They are only words, not things (against the "reales"). When

identified with words, universals are not reduced to mere "sound" (which

is also a "res"), but to the signifying power of words (against

the "nominales"). This "significatio" of words is not a

concept accompanying the word (a mere contents of mind, i.e. exclusively

subjective), but gives expression or meaning to the objective status of

the word (semantics). This status is a human convention based on real

similarities between the particulars, but these real "convenientia"

are not a "res", not "nihil" but a "quasi res" : it

is not the substance "homo" that makes human beings similar, but

the "esse hominem".

For Abelard, objectivity, found in universal propositions, is a human

convention based on real similarities between particulars. The latter

exist on their own. Ideas are the metaphysical foundation of the

similarities between objects. They are not the "ousia", "eidos",

essence or substance of things. These conventions have a special status,

for they stand between being and nothing.

The extraordinary contribution of Abelard to epistemology is that he was

able to avoid the apory of the concordia discors by introducing a

third option :

-

universale ante rem

: the universals exist before the realities they subsume :

Platonism ;

-

universale in re

: the universals only exist in the realities ("quidditas rei")

of which they are abstractions : Aristotelism ;

-

universale post rem : universals are words, abstract universal

concepts with a meaning, given to them by human convention, in which real similarities between particulars

are expressed. The latter are not

"essentia" and not "nihil", but "quasi res".

This juggling may conceal the larger

issue at hand : if extra-mental objects are particulars and mental

concepts universals, then how to think their relationship ? Does an

extra-mental foundation of universals exist ? The Greeks as well

as the Scholastics answered affirmatively. The idea of a foundation of

knowledge was still present.

For the Scholastics, given their preoccupation with God, the problem was

to know whether an objective, extra-mental reality corresponded to the

universals in the mind ? If so, then the mere concept of "God" might

entail Divine existence, as the a priori proof tries to argue. If

not, rational knowledge resulted in skepticism and Divine existence

might be argued a posteriori only. Greek rationalism was conceptual

and ontological, whereas Medieval dialectics was foundational and

logico-linguistic (psychological).

Abelard's solution involves a crucial distinction :

universals are not real, but they are words (real sounds) with a

significance referring to real similarities between real particulars.

Because of their meaning, they are more than "nothing". The foundation

of his nominalism is "the real" as evidenced by similarities between

objects, whereas the "reales" supposed an ante-rational symbiosis

between "verbum" and "res", between Platonic ideas and material objects

("methexis").

A similar Abelardian line of argumentation is found in

David Hume (1711 - 1776), ending in a skepticism preventing Kant (1724 -

1804) from sleeping (indeed, Hume rejected rationalist intuitionism and so

could not back the observed similarity between objects). When Aristotle was finally translated into Latin, Abelard could

and was recuperated by High Scholasticism.

§ 11

"Although it is clear to many

that a universal is not a substance existing outside the mind in

individuals and really distinct from them, still some are of the opinion

that a universal does in some manner exist outside the mind in

individuals, although not really but only formally distinct from them.

(...) However, this opinion appears to me wholly untenable."

Ockham : Summa totius logicae, I,

c.xvi.

With the Franciscan monk William of Ockham

(1290 - 1350), theologian & philosopher, the "via moderna"

received its most logical of defenders. Thomists, Scotists and Augustinians formed the "via antiqua". It is their

realism, Platonic (the essence is transcendent) as well as

Aristotelic (the essence is immanent), which was firmly rejected.

Instead, nominalism was promoted, but one without objective universals.

It was hence more radical than Abelard's. No reality ("quid rei")

is ever attained, but only a nominal

representation ("quid nominis").

For Ockham, the metaphysics of essences was introduced into Christian

theology and philosophy from Greek sources. So, contrary to Abelard's

moderate nominalism, his strict nominalism did not incorporate them.

There are no universal subsistent forms, for otherwise God would be

limited in His creative act by these eternal ideas. Indeed, every idea

is limited by its own individuality. This non-Christian

invention has no place in Christian thought. Universals are only "termini

concepti", final terms signifying individual things which stand for them

in propositions.

It was Peter of Spain (thirteenth century), who's exact identity

is unknown, who had distinguished between probable

reasoning (dialectic), demonstrative science & sophistical reasoning.

Ockham was influenced by this emphasis placed on syllogistic reasoning

leading to probable conclusions. Hence, arguments in philosophy (as

distinct from logic) are probable (terministic) rather than demonstrative.

Formal logic is demonstrative, whereas terministic logic is probable.

For Ockham, who took the equipment to develop this terminist logic from

his predecessors, empirical data were primordial and exclusive to

establish the existence of a thing. The validity of inferring from the

existence of one thing to the existence of another things was

questioned. He distinguished between the spoken word ("terminus

prolatus"), the written word ("terminus scriptus") and the

concept ("terminus conceptus" or "intentio animæ"). The

latter is a natural sign, the natural reaction to the stimuli of a

direct empirical apprehension. Only individual things exist. By the fact

a thing exists, it is individual. There cannot be existent universals,

for if a universal exists, it must be an individual, which is a

contradictio in terminis (for universals are supposed to subsume

individuals).

This focus on the objects which are immediately known, goes hand in hand

with the principle of economy to get rid of the abstracting "species

intelligibiles". What is known as "Ockham's Razor" was a

common principle in Medieval philosophy. Because of his frequent usage

of the principle (cf. the Franciscan vow of poverty), his name has

become indelibly attached to it. In Ockham's

version it reads : "Pluralitas non est ponenda sine

neccesitate." (plurality should not be posited without necessity).

In general terms, this principle of simplicity or parsimony is to

always prefer the least complicated explanation for an observation.

Radical nominalists, like Nicolas of Autrecourt (ca. 1300 - ca. 1350),

who belonged to the Faculty of Arts, would say no inference from the

existence of one thing to the existence of another thing could be

demonstrative or cogent, but only probable. Hence, necessity and

certainty, idolized by the

foregoing metaphysical systems, were gone. No demonstration of God's

existence was possible. Such matters have to be relegated to the order

of adherence to revealed knowledge or faith. At this point, theology and

philosophy separate and the latter becomes a "lay" activity. This is not

yet apparent in Ockham, who remains a theologian seeking to find a way to

rethink the "proof" of God's existence in merely a posteriori

terms.

Against his predecessors, Ockham accepts "being" as a concept common

to creatures and God, meaning "being" is predicable in a univocal sense

to all existent things. Without such a concept, the existence

of God could not be conceived. But, this does not mean this concept

acts as a bridge between empirical observation of creatures and the

existence of God. It is univocal in the sense it is common to a plurality of things, neither accidentally or

substantially alike (thus avoiding pantheism).

These thought bring the distinction between "scientia realis" and

"scientia rationalis" to the fore. The former is concerned with

real, individual things. He agrees with Aristotle that only individuals

exist, but rejects the doctrine that science is of the universal. The

latter are not forms realized in individuals (realities existing

extra-mentally). Real science is only concerned with universal

propositions, i.e. with their truth or falsity (for example : "Man

is capable of laughter."). To say a universal proposition in science is

"true", is to say that it is verified in all individual things of which

the "terms" of the proposition are the natural signs. The terms known by

real science stand for individual things, whereas the terms of the

propositions of rational science (like logic) stand for other terms.

Ockham's contribution is remarkable, although his terminology is still

scholastic and he considered revelation as a source of certain

knowledge.

|

With Ockham,

concept-realism is finally relinquished. The foundational approach is also

left behind. The nominal representations arrived at in real science

are only terministic, i.e. probable. They concern individuals,

never extra-mental "universals". Real science deals with true or

false propositions referring to individual things. These empirical

data are primordial and exclusive to establish the existence of a

thing. The concept ("terminus conceptus" or "intentio animæ")

is a natural sign, the natural reaction to the stimuli of a direct

empirical apprehension. Rational science is possible, but it does

not concern natural signs but other terms. |

§ 12

"Il y a déjà quelque temps que je me suis aperçu

que, dès mes premières années, j'ai reçu quantité de fausses opinions

pour véritables, et que ce que j'ai depuis fondé sur des principes si

mal assurés ne saurait être que fort douteux et incertain ; et dès lors

j'ai bien jugé qu'il me fallait entreprendre sérieusement une fois dans

ma vie de me défaire de toutes les opinions que j'avais reçues

auparavant en ma créance, et commencer tout de nouveau dès les

fondements, si je voulais établir quelque chose de ferme et de constant

dans les sciences."

Descartes, R. : Meditations, 1, §

1a.

To seek indubitable truth,

René Descartes (1596 - 1650) turned to methodological doubt. He left the Jesuit college of La Flèche and

was

ashamed of the amalgam of doubts and errors he had learned there.

Traditional philosophy consisted of various contradicting opinions,

grosso modo Platonic or Peripatetic. History was a series of moral lessons (cf. Livius) and philosophy

was still restricted to logic. The experimental method was absent, and

various authorities ("auctoritates") were studied (Galenus,

Aristotle, Avicenna, etc.). Aim was to harmonize the magisterial

contradictions (cf. the "sic et non" method). In the

interpretation of these sources, a certain creativity was at work.

However, in the mind of Cartesius, the only constructive point of his

education, so the Discourse on Method (1637) tells us, was the

discovery of his own ignorance.

This prompted him to reject all prejudices and seek out

certain knowledge. Nine years he raises doubts about various conjectures

and opinions covering the whole range of human activities. Eventually,

doubt is raised regarding three sources of knowledge :

-

authority :

as contradictions always arise between authorities a higher criterion is

needed ;

-

senses :

maybe waking experience is just a "dream" or a "hallucination" ? Can

this be or not ? Also : the senses give confused information, so a still

higher criterion is needed ;

-

reason :

how can we be certain some "malin génie" has not created us such, that

we accept self-evident reasoning although we are in reality mislead and

in fatal error ?

However far doubt is systematically applied, it

does not extend to my own existence. Doubt reveals my existence.

If, as maintained in the Principles of Philosophy, the word

"thought" is defined as all which we are conscious of as operating in us,

then understanding, willing, imagining and feeling are included. I

can doubt all objects of these activities of consciousness, but that

such an activity of consciousness exists, is beyond doubt.

Thus, the "res cogitans", "ego cogitans" or "l'être conscient"

is the crucial factor in Cartesian philosophy. Its indubitable,

intuitively grasped

truth ? Cogito ergo sum : I think, therefore I am. That I doubt

certain things may be the case, but the fact that I doubt them, i.e. am

engaged in a certain conscious activity, is certain. To say : "I doubt

whether I exist." is a contradictio in actu exercito, or a

statement refuted by the mere act of stating it.

The certainty of

Cogito ergo sum is not inferred but immediate and intuitive. It is

not a conclusion, but a certain premiss. It is not first & most certain

in the "ordo essendi", but as far as regards the "ordo

cognoscendi". It is true each time I think, and when I stop thinking

there is no reason for me to think that I ever existed. I intuit in a

concrete case the impossibility of thinking without existing. In the

second Meditation, Cogito ergo sum is true each time I

pronounce or mentally conceive it ...

Having intuited a true and certain proposition, Descartes seeks the

general criterion of certainty implied. Cogito ergo sum is true

and certain, because he clearly and distinctly sees what is affirmed. As

a general rule, all things which I conceive clearly and distinctly are

true. In the Principles of Philosophy, we are told "clear" means

that which is present and apparent to an attentive mind and "distinct"

that which contains within itself nothing but what is clear.

Although he

has arrived at a certain and clear proposition, he does not start to

work with it without more ado. Indeed, suppose God gave me a nature

which causes me to err even in matters which seem self-evident ? To

eliminate this "very slight" doubt, Descartes needs to prove the

existence of a God who is not a deceiver. Without this proof, it might

be so that what I conceive as clear and distinct, is in reality not so.

Both in the Meditations and the Principles of Philosophy,

substance is demonstrated after proving the existence of God. However, the "I" in Cogito ergo sum, is not a

transcendental ego (a mere formal condition of knowledge), but "me thinking".

Despite various contents of thought, the thing that cannot be doubted is

not "a thinking" or "a thought", but a thinking ego

conceived as a

substance. This ego is not formal, nor the "I" of ordinary discourse,

but a concrete existing "I". Descartes uncritically assumes the

Scholastic notion of substance, while this doctrine is open to doubt.

Thinking does not necessarily require a thinker, and the ego cogitans

must not be a thing which thinks, but a mere transcendental ego

accompanying every cogitation (cf. Kant).

At this point, the apory resulting from a mismanagement of the

concordia discors which animates all possible thought, reappeared

and entered modernism.

Transcendental logic makes both terms of the formal equation offered by

the Factum Rationis necessary and irreducible. In terms of

acquiring knowledge, this implies object and subject of knowledge

have to be used simultaneously. But like Plato and the "reales" after

him, Descartes eclipses the object of knowledge by inflating an ego

cogitans in terms of a substantial ego, solely reflecting on itself,

and as Leibnizean monad, without windows on the world and the alter

ego. The Spinozist definition of God and freedom being the mature

example of the substantializing (ontologizing) effect of this idealistic

reduction of the discordant concord or armed truce of thought.

"By God, I mean the absolutely infinite Being -

that is, a substance consisting in infinite attributes, of which each

expresses for itself an eternal and infinite essentiality."

Spinoza : Ethics, Part I,

definition VI.

"That thing is called 'free', which exists solely

by the necessity of its own nature, and of which the action is

determined by itself alone. That thing is inevitable, compelled,

necessary, or rather constrained, which is determined by something

external to itself to a fixed and definite method of existence or

action."

Spinoza : Ethics, Part I,

definition VII.

Because he did not rely on the object of knowledge (deemed doubtful),

Descartes rooted his whole enterprise in an ideal ego constituting the

possibility and expansion of knowledge. All idealists after him would do

the same. The end result of this reduction is a Platonic theory of

knowledge. At the end of the line, truth is identified with a consensus

between sign-interpreters (cf. Habermas).

§ 13

In his Treatise of Human Nature (1739) and Enquiry concerning

human Understanding (1748), David Hume (1711 - 1776) seeks to

develop a science of man. As Locke (1632 - 1704), he envisages a

critical and experimental foundation.

"Nature is always too strong for principle."

Hume, D. : Enquiry concerning the

Principles of Morals, 12, 2, 128.

"Perceptions" are the contents of the mind in general, divided in

impressions and ideas. The former strike the mind with vividness, force

and liveliness, whereas the latter are faint images of these in

thinking. Impressions are either of perception or of reflection. The

latter are in great measure derived from ideas.

Like Ockham, Hume is a nominalist. Real or ideal universals are not the

foundation to erect the science of man. Unlike Descartes, he is an

empirist : the senses are the foundation of knowledge. Two kinds of propositions are

possible :

-